Brickset LEGO Gift Guide - 2025

26 November 2025 • LEGOIt’s that time of the year again (where on earth has 2025 gone?!) where Brickset publish their annual holiday gift guide, in five parts split by price category. Along with the other Brickset contributors, I provided my opinion, and there’s a nice diverse range of sets across the price ranges! You can view each of the articles below, along with my pick from the available choices:

Under $25¶

- 10349 Happy Plants

$25-$50¶

- 31165 Panda Family

$50-$100¶

- 72046 Game Boy

$100-$200¶

$200+¶

- 76457 Hogsmeade Village - Collectors’ Edition

- honorary mention of 76968 Dinosaur Fossils: Tyrannosaurus rex

What would your choices be?

Pendulum 1.15 Released

6 November 2025 • Development • Swift • SwiftUI • AppsAfter quite some time without any updates, I have finally released a new version of Pendulum—version 1.15 is now available in the App Store!

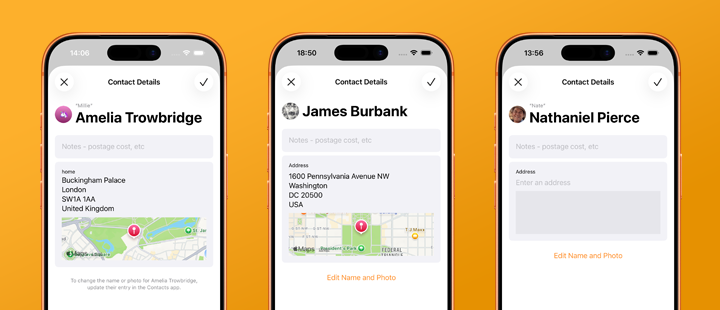

With the release of iOS 26 and it’s new Liquid Glass design language, I wanted to update Pendulum to feel more at home on the OS, and took the opportunity to change the design somewhat more drastically—at least for the main Pen Pals list. The biggest structural change was to drop the tab bar—it makes little sense when there are only two tabs—and move Settings to a top bar button. This meant I could take advantage of the new navigation transition available in iOS 26 to morph between the button and the presented sheet in a very pleasing manner.

Visually, the Pen Pal list has had a huge overhaul, with the standout change being the map in the background. This will centre itself on the location you most recently sent a letter to or received one from, and I love the way it turned out. I hope it’ll be fun for Pendulum’s users to see it pan around the world as they send and receiving their correspondence. A further update may pull the map out into its own feature, with pins for your pen pals’ locations in a more interactive manner.

Given the design now focuses rather heavily on your pen pals’ addresses, it was about time I addressed (pun intended) the inability for you to store an address against a pen pal if you’ve disabled syncing with Contacts. It’s a fairly commonly-requested feature, and this was the impetus I needed to finally get it done. Both types of Pen Pals can live happily together in Pendulum—those synced with a device contact will require you to use Contacts to update their address, and those added manually can be edited directly within the app.

The final feature in this release can be seen in the screenshot above, in Amelia’s contact details page, Pendulum will pull in any nicknames you have against your linked Contacts, with an option to prefer nicknames over full names in most of Pendulum’s UI. Amelia will be shown as Millie in the Pen Pal list and her correspondence screen, for example.

It’s been fun to have the motivation and impetus to work on Pendulum again, and I’m excited to keep adding features and iterating as I go.

Django Forms and CSV Processing

1 September 2025 • Development • Python • DjangoRecently, I’ve found myself building a number of tools that accept input data in the form of a CSV from the user, and parse and validate it before executing whatever processing is necessary for the given tool. Django’s forms provide an easy way to accept file uploads, and model forms make it trivial to store those files on disk alongside a model instance.

What I was struggling with was where to do the validation of the contents of the CSV. Forms provide some level of validation, and give the user feedback via field- or form-level errors, but in order to provide useful feedback via this mechanism the form needs to parse the CSV to validate each of its rows. This is easily doable in the field-specific clean method, such as the following, which validates that every row has an identifier field and a date field, with the date in the future (using arrow for date parsing):

import csv

import arrow

from django import forms

from django.db import models

from django.utils import timezone

class CSVUpload(models.Model):

uploaded_at = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)

csv_file = models.FileField(upload_to="csv_uploads")

class CSVUploadForm(forms.ModelForm):

class Meta:

model = CSVUpload

fields = ["csv_file"]

def clean_csv_file(self):

csv_file = self.cleaned_data["csv_file"]

try:

for row in csv.DictReader(csv_file):

if not row.get("identifier", "").strip():

raise ValueError("Missing identifier")

if arrow.get("date") <= timezone.now():

raise ValueError("Date not in the future")

except ValueError as err:

raise forms.ValidationError(f"Could not read CSV file; please ensure it is in the correct format ({err})")

return csv_file

This works fine—the form won’t pass the is_valid() check unless the data within the CSV is valid. So what’s the problem?

Well, there’s a reason we’re reading the CSV and validating the data—we want to do something with the data. The form has parsed it, but it’s thrown away any results of that parsing, leaving the view to have to do it all over again, which is less than ideal. We can’t simply return the parsed data from the clean method, because that would break Django’s FileField handling within the model form. Instead, we can take advantage of the fact that a Form instance is just that—a standard Python object, nothing special—and set an attribute on the instance with the parsed data:

class CSVUploadForm(forms.ModelForm):

class Meta:

model = CSVUpload

fields = ["csv_file"]

def clean_csv_file(self):

csv_file = self.cleaned_data["csv_file"]

parsed_data = []

try:

for row in csv.DictReader(csv_file):

row_data = {

"identifier": row.get("identifier", "").strip(),

"date": arrow.get("date"),

}

if not row_data["identifier"]:

raise ValueError("Missing identifier")

if row_data["date"] <= timezone.now():

raise ValueError("Date not in the future")

parsed_data.append(row_data)

except ValueError as err:

raise forms.ValidationError(f"Could not read CSV file; please ensure it is in the correct format ({err})")

else:

self.parsed_data = parsed_data

return csv_file

Now, within the view, we can let Django handle the model form as it should, and read the form’s parsed_data attribute to use the data from within the CSV as necessary:

class CSVUploadView(FormView):

form_class = CSVUploadForm

def is_valid(self, form):

instance = form.save()

for data in form.parsed_data:

# Use the data from the CSV, already parsed

pass

return HttpResponseRedirect(self.get_success_url())

Simple!

A Swift API Client

15 July 2025 • Development • SwiftIn a new app I’ve been toying with the idea of developing, much of the data comes from a third-party API. This isn’t uncommon nowadays, and there are multiple Swift packages out there to make interacting with a REST API easier, such as Alamofire. However, I wanted to build a minimal API client that I could use without relying on a third-party dependency, code that is under my control, and that I hopefully understand!

Using URLSession and URLRequest is relatively simple, but without some form of abstraction you’ll end up with a bunch of boilerplate code for each different request you need make. My goal was to build a simple, generic API client protocol that I could use for this particular API, but would also work for other use cases in the future.

So let’s get started!

The APIClient protocol¶

The fundamental job of an API client is to send HTTP requests to the API, and return the response. We can start by building a protocol for such a client, using the power of Swift’s Generics to accept a variety of different request objects and return a variety of different responses:

protocol APIClient {

var baseUrl: URL { get }

func send<T: APIRequest>(_ request: T) async throws -> T.Response

}

I’ve also added a baseUrl parameter, to allow the client to specify a single base URL for the API calls.

You’ll note that I’ve used a type I haven’t yet defined, APIRequest, so let’s do that now. A request needs a handful of properties:

- the resource the request relates to;

- the HTTP method to use;

- any querystring parameters;

- any request body;

- any custom headers.

We can define a protocol to handle these requirements:

protocol APIRequest: Encodable {

associatedtype Response: Decodable

var resourceName: String { get }

var method: String { get }

var parameters: [URLQueryItem] { get }

var body: Data? { get }

var headers: [String: String] { get }

}

extension APIRequest {

var parameters: [URLQueryItem] { [] }

var method: String { "GET" }

var body: Data? { nil }

var headers: [String: String] { [:] }

}

There are sensible defaults for most of these properties (such as defaulting to a GET request with no body, no parameters, and no custom headers), so an extension to the protocol can define these.

Here we also define an associated type called Response, which must be Decodable. This allows us to tie an APIRequest to a struct representing the response it expects, and is used as the return type in the function signature of send in the APIClient protocol above.

So what’s missing? The actual functionality of the send method, of course!

extension APIClient {

func send<T: APIRequest>(_ request: T) async throws -> T.Response {

let endpointRequest = self.endpointRequest(for: request)

let (data, _) = try await URLSession.shared.data(for: endpointRequest)

return try JSONDecoder().decode(T.Response.self, from: data)

}

}

Just three simple lines:

- Call another method,

endpointRequest(for:), to generate aURLRequestobject (more on this below). - Execute the request and await the response.

- Decode that response from JSON into the request’s

Responsestruct.

This is a nice short method for a couple of reasons. First, it doesn’t do any error handling—that’s left as an exercise for the reader to decide how to handle the various possible network request errors or response decoding errors. Secondly, the conversion of the APIRequest object into a URLRequest object is handed off to another method, so let’s write that now:

extension APIClient {

func endpointRequest<T: APIRequest>(for request: T) -> URLRequest {

guard let baseUrl = URL(string: request.resourceName, relativeTo: self.baseUrl) else {

fatalError("Invalid URL for resource \(request.resourceName)")

}

var components = URLComponents(url: baseUrl, resolvingAgainstBaseURL: true)!

components.queryItems = request.parameters

var urlRequest = URLRequest(url: components.url!)

urlRequest.httpMethod = request.method

if let body = request.body {

urlRequest.httpBody = body

}

for (header, value) in request.headers {

urlRequest.setValue(value, forHTTPHeaderField: header)

}

return urlRequest

}

}

This does a couple of things:

- Adds the request’s

resourceNameto the API client’sbaseUrlto generate the full URL for the request. - Adds any parameters from the request a

URLComponentsobject based on the generated URL. - Creates a

URLRequestobject with the full URL (that will now include any querystring parameters). - Sets the HTTP method, body, and headers from the

APIRequestobject. - Returns the fully configured

URLRequest.

Now we’re ready to actually use the API client!

Using the APIClient protocol¶

First, we need to create a concrete class from the protocol, and define our API’s base URL:

class MyAPIClient: APIClient {

let baseUrl = URL(string: "https://example.com/api/v3/")!

static let shared = MyAPIClient()

}

In this example API, there are two endpoints:

/api/v3/checkKey- returns the status of the API key provided./api/v3/getKeyUsageStats- returns the usage stats of the API key provided.

In both cases, the API key must be provided as a querystring parameter called apiKey—for example, /api/v3/checkKey?apiKey=12345.

We can write the APIRequest structs to represent both of these calls:

let API_KEY_PARAMETER = URLQueryItem(name: "apiKey", value: "MY_API_KEY")

struct ExampleCheckKeyRequest: APIRequest {

typealias Response = ExampleCheckKeyResponse

var resourceName: String = "checkKey"

var parameters: [URLQueryItem] = [API_KEY_PARAMETER]

}

struct ExampleGetKeyUsageRequest: APIRequest {

typealias Response = ExampleGetKeyUsageResponse

var resourceName: String = "getKeyUsageStats"

var parameters: [URLQueryItem] = [API_KEY_PARAMETER]

}

Note that they both specify their associated Response types—remember, these need to be Decodable structs that can be used as the destination for the returned JSON from each API call. We can write these as follows:

// checkKey returns a JSON object with a `status` string and optional `message`

struct ExampleCheckKeyResponse: Decodable {

let status: String

let message: String?

}

// getKeyUsage returns a JSON object with a `status` string, an optional `message`,

// and a `matches` integer with the number of times the key has been used recently

struct ExampleGetKeyUsageResponse: ExampleAPIResponse {

let status: String

let message: String?

let matches: Int?

}

With the request and response types set up, all that’s left is to add helper methods to our actual client, so that the rest of our code doesn’t need to know or understand the requests themselves:

extension ExampleAPIClient {

func checkKey() async throws -> ExampleCheckKeyResponse {

return try await self.send(ExampleCheckKeyRequest())

}

func getKeyUsage() async throws -> ExampleGetKeyUsageResponse {

return try await self.send(ExampleGetKeyUsageRequest())

}

}

And finally, call them!

do {

let checkKeyResult = try await ExampleAPIClient.shared.checkKey()

print("\(checkKeyResult)")

let getKeyUsageResult = try await ExampleAPIClient.shared.getKeyUsage()

print("\(getKeyUsageResult)")

} catch {

print("Error: \(error.localizedDescription)")

}

// Prints:

// ExampleCheckKeyResponse(status: "success", message: nil)

// ExampleGetKeyUsageResponse(status: "success", message: nil, matches: Optional(2))

Simples, no?

So far, these are very simple requests, and I haven’t included much (if any!) error handling—but it feels like a good start to a simple API client interface I can use throughout my apps, with little code, and code that actually feels maintainable.

Birds and Angles: Dabbling in Django Components

24 March 2025 • Development • Python • DjangoThe Django template language is great. It’s been one of the core pillars of Django’s popularity since the beginning—a simple, easy-to-use templating language that tries to give you just enough power to do what you need without having to think too hard.

However, there are more modern ways of thinking about template rendering that the DTL lacks: notably, support for components—splitting templates into smaller reusable chunks, that can each take their own contexts and render just what they need to. There’s always been the include tag, but it’s rather limited.

A number of third-party libraries have sprung up, such as django-bird, django-cotton, and django-components, to name just a few. Until now, I’ve never used any of them, and made do with the include tag wherever I needed to reuse a snippet of a template—however, I decided to take a look and see what all the fuss was about on a small project at work.

The design of a page I was building called for some repeated boxes displaying a couple of pieces of data for different time periods, shown below:

While this could relatively easily be done with an include, this seemed like the perfect opportunity to try one of the component libraries. I chose django-bird, as the way it functions seems to gel best with the way my brain thinks about components. I ended up with the following component:

{# templates/bird/request-stats-summary-button.html #}

{% load humanize %}

{% bird:prop period %}

{% bird:prop this_period %}

{% bird:prop active_users=999 %}

{% bird:prop totals=999 %}

<div

class="card card-hover me-sm-3 rounded border {% if props.period == props.this_period %}bg-primary text-light{% else %}card-hover-bg-primary{% endif %}"

>

<div class="card-body pb-2 pt-2 shadow-sm">

<h6 class="card-title {% if props.period != props.this_period %}text-muted{% endif %} text-uppercase fw-normal">

{{ slot }}

</h6>

<p class="mb-0 d-flex align-items-center">

<i class="fas fa-user {% if props.period == props.this_period %}text-light{% else %}text-primary{% endif %} fs-5"></i>

<span class="fs-3 ms-1">{{ props.active_users|intcomma }}</span>

<i class="fas fa-mouse-pointer ms-3 {% if props.period == props.this_period %}text-light{% else %}text-primary{% endif %} fs-5"></i>

<span class="fs-3 ms-1">{{ props.totals|intcomma }}</span>

</p>

</div>

</div>

You’ll notice the use of four “props” to pass data through, as well as the {{ slot }} variable to capture the contents of the component. I updated the main template to use the component:

{% bird request_stats_summary_button period=period this_period="today" active_users=active_users.today totals=totals.today %}

Today

{% endbird %}

{% bird request_stats_summary_button period=period this_period="this_week" active_users=active_users.week totals=totals.week %}

This Week

{% endbird %}

{% bird request_stats_summary_button period=period this_period="this_month" active_users=active_users.month totals=totals.month %}

This Month

{% endbird %}

{% bird request_stats_summary_button period=period this_period="this_year" active_users=active_users.year totals=totals.year %}

This Year

{% endbird %}

And it worked great!

I originally picked django-bird because I liked how it used standard DTL tags, and didn’t require any custom template parsers. However, in actual use, I don’t like that I can’t wrap DTL tags to multiple lines, which ends up with the bird lines quickly becoming unwieldy. There’s a forum post and ticket about supporting new lines in DTL tags, but that won’t happen any time soon.

This is where another new-to-me package comes in—dj-angles! The main purpose of this package is to provide a web-component-style template tag interface to the built-in DTL template tags, as demonstrated quite neatly in their docs. This is done by adding a new template loader that parses the alternative syntax. However, what’s of interest to me is that they also provide native integration with django-bird, allowing us to use the more compact (and new-line-compatible!) style tags with bird components.

A couple of settings later, and we can reference the above components in a way that really seems to click for me:

<dj-request-stats-summary-button

period=period

this_period="today"

active_users=active_users.today

totals=totals.today

>

Today

</dj-request-stats-summary-button>

<dj-request-stats-summary-button

period=period

this_period="this_week"

active_users=active_users.week

totals=totals.week

>

This Week

</dj-request-stats-summary-button>

<dj-request-stats-summary-button

period=period

this_period="this_month"

active_users=active_users.month

totals=totals.month

>

This Month

</dj-request-stats-summary-button>

<dj-request-stats-summary-button

period=period

this_period="this_year"

active_users=active_users.year

totals=totals.year

>

This Year

</dj-request-stats-summary-button>

It’s more verbose in number of lines, but much more readable!

Yes, I’m aware that this is the sort of thing that django-cotton and other template libraries provide automatically, but I’ve come to quite like django-bird. Perhaps I’ll swap to one of the others one day, but for now, I’m enjoying what the combination of birds and angles can give me.

There’s only one main issue I have with django-bird, and that’s how it doesn’t parse DTL filters in values passed as properties or attributes. For example, the following component reference:

{% bird button badge_count=users|length %}Users{% endbird %}

will result in the badge_count prop inside the button component being set to the string "users|length", which is not the desired result at all. I have an open issue and associated draft PR on the repo, so hopefully we’ll be able to get the feature into the library before too long.

Brickset LEGO Gift Guide - 2024

27 November 2024 • LEGOOnce again Brickset have published their annual holiday gift guide, in five parts split by price category. Huw asked for my opinion, along with the other Brickset contributors, and I think most of us made some pretty good choices! You can view each of the articles below, along with my pick from the available choices:

- Less than $25 - 31147 Retro Camera

- $25-$50 - 31154 Forest Animals: Red Fox

- $50-$100 - 43249 Stitch

- $100-$200 - 31212 The Milky Way Galaxy

- $200+ - 10326 Natural History Museum

What would your choices be?

Static Files in Django: An Introduction

3 April 2024 • Development • Python • DjangoSome of the most common recurring questions in the Django Discord revolve around static files, why they’re not loading when they should, or how to configure them and what should be responsible for serving them. I thought I’d write up a bit of an introduction to static files in Django, which will hopefully be a little more approachable to beginners than the official docs (as excellent as they are), and serve as a starting point for diagnosing problems with them.

What are static files?¶

Static files are files served as part of your Django application whose contents do not change from user to user or request to request—they are not dynamic. By far the most common examples are the stylesheets (CSS), Javascript, and images that are required for the application to look and function correctly in the browser, but they could just as easily be other things—JSON files of data that doesn’t change, for example.

Static files are not any files that your users upload, such as profile pictures, or other content. Those are referred to by Django as media files, and are handled differently.

Static files terminology¶

There are three key pieces of information to know about Django’s static files:

- the directories you store them in during development of the project,

- the URL they are served under when requested by the browser, and

- the directory (note: singular) they are collecting into as part of deploying the app.

These are three distinct, but interrelated, pieces of the puzzle, and they each have different settings to adjust or define their behaviour in settings.py.

Where do I put my static files?¶

By default, Django will look for your static files in a directory named static inside each app directory in INSTALLED_APPS, and without any additional configuration this is the only place it will search. For many, that’s enough.

Others may wish to store some static files outside any one particular app, because they may be relevant globally to the project and there isn’t a single app that fits them best. This can be done by creating a new directory somewhere (often, named static at the same level as manage.py), and adding a new setting to settings.py:

STATICFILES_DIRS = [os.path.join(BASE_DIR, "static")]

The STATICFILES_DIRS setting tells Django to look for static files in those additional directories, as well as within each individual app directory.

What URL do I use to request my static files from the browser?¶

The single setting, STATIC_URL, defines the URL prefix that Django expects the static files to be available under when the browser requests them. This is entirely independent from their actual location on the file system as discussed above.

Django suggests a perfectly reasonable default for this: "static/". It must end in a slash.

When running your application, Django will expect the static files to be available under that URL. For example, a file in a directory my_app/static/css/styles.css would correspond to a URL of /static/css/styles.css.

When referencing static files in templates, such as using a link or script tag to include CSS or JavaScript in HTML, Django provides a template tag in the static library to automatically convert a relative static file name into its full URL path. For example, to include the above CSS file:

{% load static %}

…

<link href="{% static "css/main.css" %}" rel="stylesheet">

This would result in the following HTML output:

<link href="/static/css/main.css" rel="stylesheet">

So, how does Django map the URL to the actual file on the file system?¶

And what’s this third key point I mentioned above, the single static directory?

The answer to this differs depending on how you’re running Django; in development or production.

Serving static files in development¶

During development, it’s acceptable for Django to serve the static files itself. Normally, this job would be handed off to a web server or proxy, as there is no benefit to spinning up the full Django application process just to chuck some static CSS back to the browser, but during development it is really not worth having to set that all up.

When running Django with the development server (manage.py runserver) and DEBUG=True, Django will automatically add a new URL path to your URL patterns that matches the value of STATIC_URL, and search the various directories mentioned above for matching files to serve whenever a request comes in. This means that by only setting a STATIC_URL to something sensible, Django will automatically be able to serve the CSS, JavaScript, and images stored in any static folder inside each INSTALLED_APPS directory, and any folders pointed to by STATICFILES_DIRS. That’s usually enough for development purposes.

Serving static files in a production environment¶

However, as mentioned above, it’s inefficient to have Django serve these files itself when deployed in a production environment. Instead, that responsibility is usually handed off to a web server or proxy that sits in front of Django, such as nginx. So how does this proxy know where to find the static files?

The answer is in the STATIC_ROOT setting. This should be pointed to a directory on the file system that, once deployed, both the Django application and the proxy can access.

What should be in that directory? Nothing, to start with. Part of the deployment process should be to run manage.py collectstatic, a built-in management command which runs round all the various folders the static files live in (see the first point above) and copies them into the STATIC_ROOT directory, ready for the proxy to efficiently serve them.

The final part of the puzzle is to correctly configure the proxy so that requests for any path matching the prefix defined in STATIC_URL map onto the folder defined in STATIC_ROOT. This way, once collectstatic has been run, all the discrete parts of the application point together at a single, efficiently-served directory of static files.

Troubleshooting missing static files¶

Follow these steps to help diagnose why styles may not be loading, images not showing up, or any other static files not appearing correctly in the browser.

- Ensure the file is in either a directory named

staticunder one of yourINSTALLED_APPS, or in a directory pointed at bySTATICFILES_DIRS. - Make sure

STATIC_URLis configured and ends in a/. - Ensure you are using the

{% static "relative/path/to/file" %}template tag wherever you reference static files in your templates. - If you are developing and using

runserver, make sureDEBUG=True. Restart therunserverto be sure it picks up any changes you may have made. - If the app is deployed, make sure your

STATIC_ROOTpoints to a directory on the file system, you have runcollectstatic, and whatever proxy that fronts Django is properly configured to pointSTATIC_URLat theSTATIC_ROOTdirectory.

Note also that browsers will cache static files, so a forced refresh can help debug. This is usually done with Ctrl-F5, but varies from browser to browser.

Further reading¶

Hopefully this should provide a basic introduction to static files in Django, with enough information to get you up and running and help diagnose when static files aren’t working as you expect. For further reading, I suggest looking at the following resources:

- Django’s documentation on:

- Managing static files

- Static files settings. Take note of the additional options we didn’t discuss here, such as

STATICFILES_FINDERS. - The

staticfilesapp.. If this app is not included inINSTALLED_APPS, none of the above will work. - Deploying static files, including how to deploy to a CDN rather than a local directory.

- Libraries such as Whitenoise for situations where configuring a proxy in front of Django isn’t possible.

Review: 31154 Forest Animals: Red Fox

12 March 2024 • LEGO ReviewsLEGO’s got some really strong Creator 3-in-1 sets out this year, and 31154 Forest Animals: Red Fox is one of the best. You can build a fox, an owl, or a squirrel, and all three models are truly excellent.

31154 Forest Animals: Red Fox doesn’t disappoint; all three models are fantastic, were a joy to build, and look great on display. Each manages to capture the unique characteristics of the woodland creatures, and the articulation makes them quite satisfying to pose in the way that you want.

Review: 31148 Retro Roller Skate

15 December 2023 • LEGO ReviewsOnce again LEGO are coming up with some very creative 3-in-1 sets for their first wave of 2024:

I’m a big fan of the 3-in-1 range. Lately LEGO have been knocking it out of the park with so many of these sets, and this one held great promise. I love the colour scheme, and the roller skate is a brilliant build. It’s a decent size, feels solid in the hand, and although it’s not a vehicle, pushing it around is quite satisfying. It’s just a shame there’s only one—a pair would have been fantastic!

Anatomy of a Configurable Widget

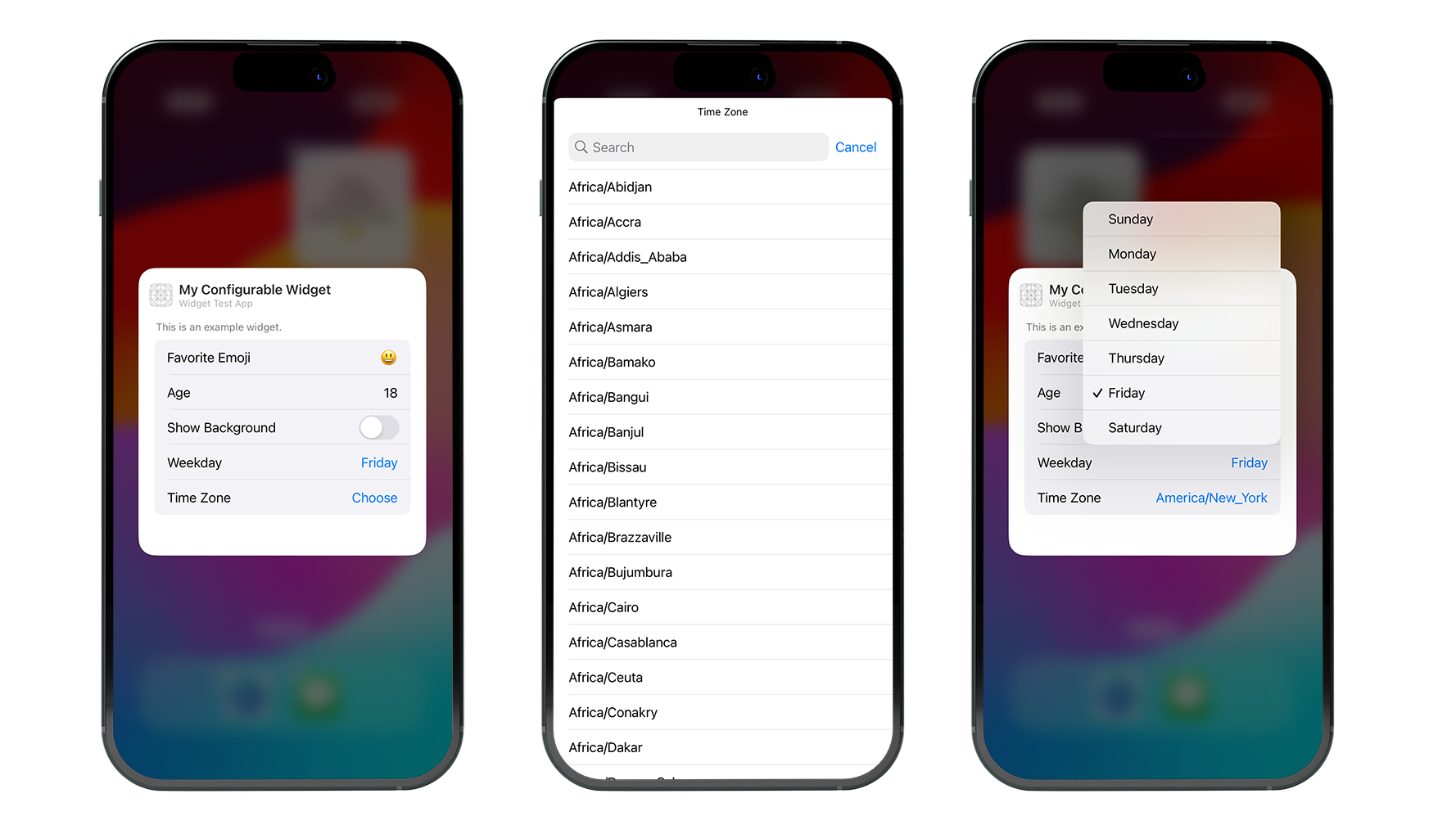

7 October 2023 • Development • Swift • SwiftUIIn my previous post, Anatomy of a Widget, I outlined my basic understanding of building a simple widget in Xcode. These were the most trivial widgets possible: they provided no options, and certainly no interactivity as introduced with iOS 17. In this post, I’m going to write up my (also limited) understanding of the parts that need to be added to provide configurable options within the widget—in other words, those the user sees when they long press on a widget and hit “Edit”.

The previous post introduced the concept of the the timeline entry, the timeline provider, the widget’s view, the widget definition, and the widget bundle. We’ll be adding one more, the configuration intent, and tying it in to the rest.

- The Configuration Intent

- Updating the Timeline Entry

- Updating the Timeline Provider

- Updating the Widget’s View

- Configuration Intent Parameters

The same major caveat as before continues to apply: I still do not fully understand widgets, or really know how to build them properly. Nor do I understand interactive widgets that come in with iOS 17. But, hopefully, my knowledge will increase and I can update these posts as I learn more! Please do not hesitate to let me know about anything I write here that’s misleading or factually incorrect.

The Configuration Intent¶

iOS apps use what Apple refers to as “intents” to tell other parts of the system what the app can do—such as Siri, or Shortcuts. The same mechanism is used by widgets to define what options are available, and we do this using a struct conforming to WidgetConfigurationIntent. This struct needs to hold all the parameters available to the user in the widget’s edit menu. For example, a very simple widget intent could look like the following:

import WidgetKit

import AppIntents

struct MyConfigurationIntent: WidgetConfigurationIntent {

static var title: LocalizedStringResource = "Configuration"

static var description = IntentDescription("This is an example widget.")

@Parameter(title: "Favourite Emoji", default: "😃")

var favouriteEmoji: String

}

This is about as basic as it gets, providing a single string parameter that will be exposed in the edit menu via a text field, with a sensible default. I’ll go through some other parameter types available later.

For now, we need to propagate the configuration intent throughout the rest of the widget’s stack.

Updating the Timeline Entry¶

The timeline entry is responsible for holding all the information the widget’s view needs to render for a given point in time. We need to update this to also hold the configuration intent. I will be using the example code from the previous post, and adding/amending it as necessary:

struct MyWidgetEntry: TimelineEntry {

let date: Date

let text: String

let configuration: MyConfigurationIntent

}

Updating the Timeline Provider¶

Because the timeline entries are created by the timeline provider, we need to update this to include the configuration intent too. This time, we also need to change from conforming to the basic TimelineProvider protocol to the mode advanced AppIntentTimelineProvider protocol, which also necessitates changing the method signatures of the three methods, placeholder, getSnapshot, and getTimeline.

struct MyTimelineProvider: AppIntentTimelineProvider {

func placeholder(in context: Context) -> MyWidgetEntry {

MyWidgetEntry(date: Date(), configuration: MyConfigurationIntent())

}

func snapshot(for configuration: MyConfigurationIntent, in context: Context) async -> MyWidgetEntry {

MyWidgetEntry(date: Date(), configuration: configuration)

}

func timeline(for configuration: MyConfigurationIntent, in context: Context) async -> Timeline<MyWidgetEntry> {

var entries: [MyWidgetEntry] = []

// Generate a timeline consisting of five entries an hour apart, starting from the current date.

let currentDate = Date()

for hourOffset in 0 ..< 5 {

let entryDate = Calendar.current.date(byAdding: .hour, value: hourOffset, to: currentDate)!

let entry = MyWidgetEntry(date: entryDate, configuration: configuration)

entries.append(entry)

}

return Timeline(entries: entries, policy: .atEnd)

}

}

For the placeholder method, the timeline provider isn’t handed a configuration, so it has to create one to pass to the timeline entry. For the other two methods, however, the first argument passed is a MyConfigurationIntent struct representing the options the user has selected in the widget edit view, and we can pass this directly to the timeline entry.

Updating the Widget’s View¶

The only thing left to do is update the widget’s View to make use of the options provided by the configuration intent. In this case, we can use the favouriteEmoji parameter, as it’s the only one provided by our very simple intent:

struct MyWidgetView : View {

var entry: MyWidgetEntry

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text(entry.date, style: .time)

Text(entry.text)

Text("Favourite Emoji:")

Text(entry.configuration.favouriteEmoji)

}

}

}

And that’s it! The widget now allows the user to customise its view by presenting an edit menu with a bunch of parameters. The user-chosen values for these parameters are passed into the View as a Configuration Intent parameter via the timeline entry, and the View can make use of them as it wishes.

Configuration Intent Parameters¶

Above, we saw a very simple configuration intent parameter of a string:

@Parameter(title: "Favourite Emoji", default: "😃")

var favouriteEmoji: String

The title is the name of the parameter as shown to the user in the edit view of the widget, and the default you provide is what the parameter is set to when the user hasn’t edited the widget and entered something else. You can view the WidgetConfigurationIntent documentation for more options that are available, such as how to control the order the parameters appear in the widget edit view or define those which depend on others.

Adding other type of data is easy, such as asking for an integer:

@Parameter(title: "Age", default: 18)

var age: Int

Or a boolean:

@Parameter(title: "Show Background", default: false)

var showBackground: Bool

You can also present the user with a choice of options by conforming to DynamicOptionsProvider:

struct IntegerOptionsProvider: DynamicOptionsProvider {

let count: Int

let defaultInteger: Int

func results() async throws -> [Int] {

Array(0...count)

}

func defaultResult() async -> Int? {

defaultInteger

}

}

...

@Parameter(title: "Hour", optionsProvider: IntegerOptionsProvider(count: 24, defaultInteger: 16))

var hour: Int

More complicated data types can be represented by conforming to various protocols, such as AppEnum to provide users with a choice based on an enum:

enum Weekday: Int, AppEnum {

static var typeDisplayRepresentation: TypeDisplayRepresentation = "Weekday"

case Sunday = 1

case Monday = 2

case Tuesday = 3

case Wednesday = 4

case Thursday = 5

case Friday = 6

case Saturday = 7

static var caseDisplayRepresentations: [Weekday: DisplayRepresentation] = [

.Sunday: "Sunday",

.Monday: "Monday",

.Tuesday: "Tuesday",

.Wednesday: "Wednesday",

.Thursday: "Thursday",

.Friday: "Friday",

.Saturday: "Saturday"

]

}

...

@Parameter(title: "Weekday", default: .Friday)

var weekday: Weekday

Or by conforming an struct to AppEntity and the associated EntityQuery, you can add support for arbitrary data types, which is the most powerful but complicated option, such as this example for adding a time zone choice to the widget:

struct TimeZoneQuery: EntityStringQuery {

private func convertToWidgetTimeZone(identifiers: [String]) -> [WidgetTimeZone] {

identifiers.compactMap { TimeZone(identifier: $0) }.map { WidgetTimeZone(timezone: $0) }

}

func entities(matching string: String) async throws -> [WidgetTimeZone] {

return convertToWidgetTimeZone(identifiers: TimeZone.knownTimeZoneIdentifiers.filter { $0.localizedStandardContains(string) })

}

func entities(for identifiers: [String]) async throws -> [WidgetTimeZone] {

return convertToWidgetTimeZone(identifiers: TimeZone.knownTimeZoneIdentifiers.filter { identifiers.contains($0) })

}

func suggestedEntities() async throws -> [WidgetTimeZone] {

return convertToWidgetTimeZone(identifiers: TimeZone.knownTimeZoneIdentifiers)

}

}

struct WidgetTimeZone: Equatable, Hashable, AppEntity {

typealias DefaultQuery = TimeZoneQuery

static var defaultQuery: TimeZoneQuery = TimeZoneQuery()

static var typeDisplayName: LocalizedStringResource = LocalizedStringResource("TimeZone", defaultValue: "TimeZone")

static var typeDisplayRepresentation: TypeDisplayRepresentation {

TypeDisplayRepresentation(stringLiteral: "TimeZone")

}

public var displayRepresentation: DisplayRepresentation {

DisplayRepresentation(title: .init(stringLiteral: id))

}

var id: String { timezone.identifier }

var timezone: TimeZone

}

...

@Parameter(title: "Time Zone")

var timeZone: WidgetTimeZone?

An extension of the Configuration Intent protocol is also what powers the interactive widgets available in iOS 17. Hopefully, once I’ve figured those out a little more, a future post will cover the basics of them too!